The science fiction trope of humans superpowered by computer and bionic implants is fast becoming a reality, and today, a startup hoping for a role in how that plays out is announcing some funding.

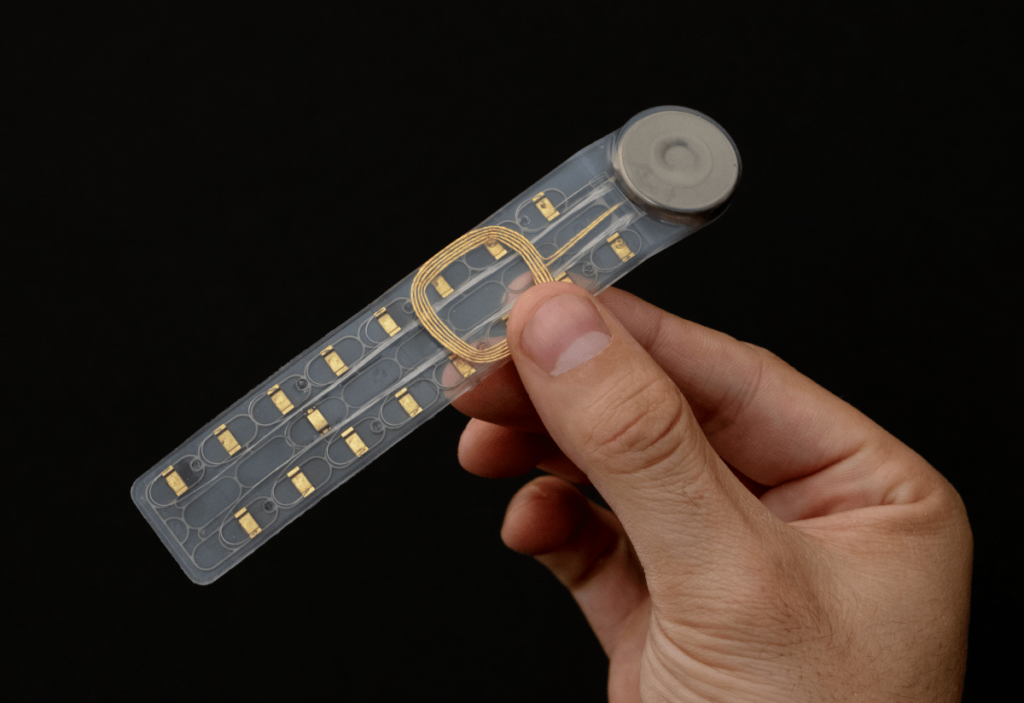

Phantom Neuro, which is developing a wristband-like device that gets implanted under the skin to let a person control prosthetic limbs, has raised $19 million to fund its next stage of development.

The startup has already hit a few important milestones for a medical tech startup. It has received two FDA designations, one as a Breakthrough Device and for TAP. The latter is selective and is issued through the agency’s medical device accelerator program, designed to streamline Phantom’s “path to commercialization,” the company said.

The company also has some operational wins. Its technology is built on the concept of the phantom limb — amputees often feel they still have a physical limb due to the nerve endings they still have that would have connected to that limb.

Phantom claims that its “Phantom X” software, which lets its strip “read” those nerve impulses and translate them into the movement of the attached prosthetic, showed 94% accuracy across 11 hand and wrist movements in a recent non-invasive “ASCENT” study. Phantom says when the strip is implanted under the skin, the accuracy is even higher. The company claims that users can restore as much as 85% of functionality with just 10 minutes of calibration.

Ottobock, a German maker of prosthetics and other medical devices, is leading the round as a strategic backer. Also participating were the company’s previous investors Breakout Ventures, Draper Associates, LionBird Ventures, Time BioVentures, and Risk and Return (aka Rsquared), plus new investors Actual VC, METIS Innovative, e1 Ventures, Jumpspace, MainSheet Ventures, and Brown Advisory. Other investors in the startup include Johns Hopkins and Intel.

Phantom has raised $28 million to date and is not disclosing its valuation.

From stress fractures to scaled impact

Austin, TX-based Phantom is the brainchild of Dr. Connor Glass, a polymath-big thinker type whose eyes widen when he talks about his past and his visions for the future.

Growing up in Oklahoma, Glass says he had a kind of intensity of purpose from early on. His plan, he said, was to join the military when he grew up “to make a scaled impact on the world.”

As a university student, that took the form of joining the ROTC, where he discovered a harsh reality: he had a tendency to get repeat stress fractures. That would ultimately limit what he wanted to do in the military, he realized.

Thinking back to an experience he had when he was younger, observing a brain operation (his dad was friends with the neurosurgeon, he said, and apparently he was allowed in to sit in the OR…), Glass had an “a-ha!” moment, and made a pivot.

He dropped his political science major and went pre-med instead. His scaled impact, he decided, would be to become a neurosurgeon and help people with even more serious limb issues than mere repeat stress fractures.

Glass eventually graduated from medical school in Oklahoma, and — inspired by science fiction, YouTube and actual scientific research — landed at Johns Hopkins, doing cutting-edge medical research in the field of brain implants used to control physical movement.

There, he had one more epiphany: He saw that the field of brain implants was still largely nascent, unwieldy and too imprecise, on top of being very invasive.

“There’s a team of PhD students frantically running around, plugging things in and typing on computers,” he said of the typical environment in those labs. “There are massive cables that had to be, you know, stuck onto the implants that came out of the patient’s skull, which allowed the signals to get out of the implants and go to the limbs. I was struck by the fact that, well, this isn’t scalable at all. This is purely proof of concept.”

With his focus still on “sweeping impact” and scale, he shifted again to looking at the wider neural network in the body. That led him to focus on nerve endings, the concept of the phantom limb, and how to bring these into the physical world by understanding what those nerves are trying to signal. That’s how Phantom Neuro came to be.

If you are wondering how willing people might be to implant a plastic strip inside their limbs to control prosthetics more easily, it’s not exactly unchartered territory. There are already procedures in place for therapies that place implants on spinal cords, for birth control, to augment breasts, to monitor heart activity and, yes, to develop brain-computer interfaces. Phantom Neuro believes that this is just one more step on that trajectory, and hopes the market sees it that way, too.

The company plans to make its tech available first for prosthetic arms, and plans to add support for legs after that. The applications of the tech go beyond amputees, too, since it might also be used for controlling robots remotely, and — since we’re living in the age of AI training — to potentially use that data for helping robots learn to move in more human-like ways. All of that is very much in the distant future, however.

With Phantom focused on building the nerve-prosthetic interface and technology, there is an obvious hand-off that will require equally impressive R&D in the form of the “edge devices” — the prosthetics themselves. Glass said the idea is for Phantom to work with a number of companies’ products, but getting involved with Ottobock, one of the big developers of these, is obviously a smart move to get closer to that development.

“I think that Phantom is making good progress in the neural interface between prosthetics and the human body,” Dr Arne Kreitz, Ottobock’s CFO, said in an interview. “That’s why we invested. It’s an interesting approach and not too invasive. There is a lot going on here at the moment from brain interfaces and less invasive methods.”