For fusion power aficionados, hitting “breakeven” is something of a Holy Grail: the point at which a fusion reaction produces more power than was required to ignite it. Only one scientific experiment, at the National Ignition Facility, has accomplished that feat, and it took over a decade of tweaking the system to achieve the monumental result.

“The day of the NIF result was, obviously, this incredibly celebrated scientific result. They all deserve Nobel Prizes,” Benj Conway, co-founder and CEO of Zap Energy, told TechCrunch. “But you know, the day after, the question is, well, so what? What next?”

And while the NIF has managed to improve upon its first result, its device is something of a dead end. It was meant to probe the limits of physics, not sell power to the grid.

For a startup like Zap, “so what” needs to have a better answer.

Zap’s answer, so far, is a new device it calls Century, for which it recently raised a $130 million Series D. After keeping Century under wraps for several months, the startup gave TechCrunch a peek under the hood, sharing exclusive details about its operation and what it hopes to learn by using it.

Zap is taking a unique approach to fusion power known as sheared-flow-stabilized Z-pinch. Instead of using magnets or lasers to squeeze the plasma, it sends a bolt of electricity through a plasma stream. That current generates a magnetic field which compresses the plasma — the pinch — and ends up with fusion. The company had been studying the phenomenon through a series of devices at its facilities in Washington State.

But Century isn’t just another physics testbed, Conway said.

“Our focus is not just on physics, but also on systems engineering. We’re not just a plasma physics company. We’re developing all of the key enabling technologies that we’re going to need to deliver commercial fusion. We think that doing all of this in parallel — everything all-together, all-at-once type thing — is the fastest way to actually deliver a commercial product,” he said. “Century is the incarnation of that.”

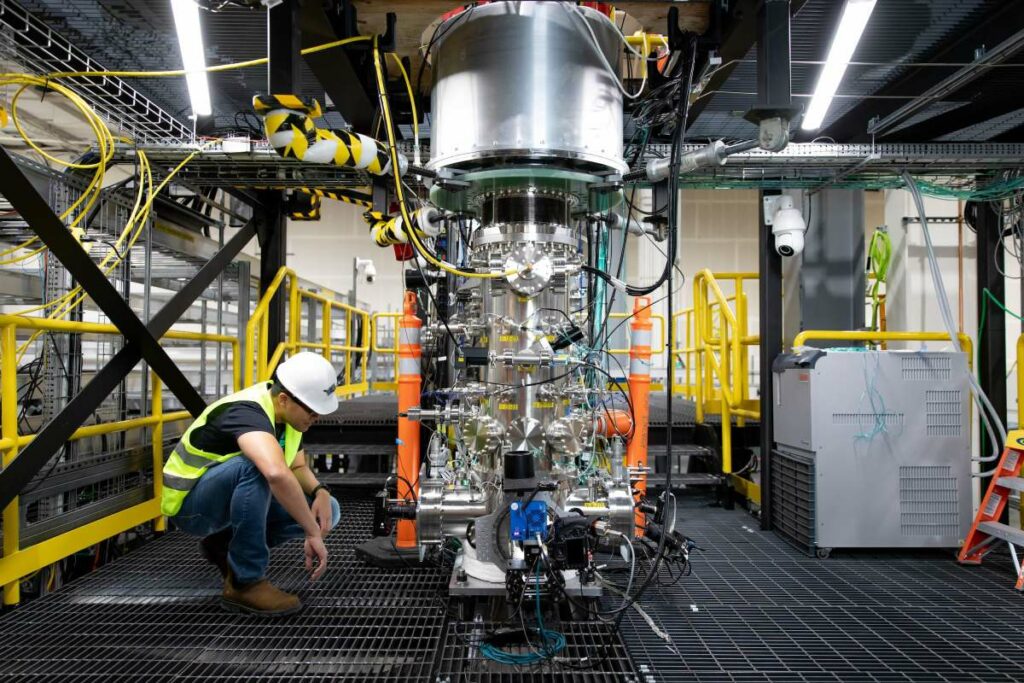

The demonstration device stands about a story and a half tall, and the reaction chamber inside is the size of a domestic water heater. Altogether, the key components occupy as much space as a double decker bus, and Zap thinks its commercial-scale module, which should produce 50-megawatts of electricity, will occupy a similar footprint.

To remain on track to a commercial power plant, Zap needs to hit three milestones: First, it needs to be able to generate high-voltage pulses frequently and continuously. A few weeks after it was turned on this summer, Century fired 1,080 consecutive pulses. So far, so good.

The next step is to demonstrate the technology for the Department of Energy, running the device for more than two hours by firing at ten second intervals to generate at least 1,000 plasma pulses. Ultimately, to operate as a commercial power plant, Zap’s reactor will need to spark 10 pulses per second for months on end.

After Century completes the demonstration for the Department of Energy, the team will surround the reaction chamber with liquid bismuth. The molten metal will protect other parts of the device while absorbing heat that, in a commercial implementation, can be used to generate electricity. Century will be able to hold over one metric ton of the liquid metal, though when the loop is first installed in November, it’ll start with 70 kg.

Lastly, the company needs to ensure that its electrodes, the parts that generate the electric pulses, can withstand the heat and particles unleashed by each fusion reaction. Those parts won’t last forever; all commercial power plants have to undergo maintenance at some point. The question is usually how frequently and for how long. Zap needs to ensure its most vulnerable parts can last long enough to make financial sense for power producers.

By next year, the company will increase the amount of electricity that’s delivered to the reaction chamber until it hits 100 kilowatts. Along the way, Conway expects the company will revamp the Century bit by bit. “Even though Century is one platform, one name, within it are multiple generations,” he said. “We iterate within the iterations.”

If Century works as planned, “my hope would be that we’re building a demo well in this decade,” Conway said. And if that goes well, commercial power plants should follow in the early 2030s.

That’s a lot of “ifs,” something Conway acknowledges. “I’m convinced that when we cut the ribbon on our first power plant and we think about the hardest problems we’ve had to solve in the last five years, my guess is plasma physics and gain is on the list. But I bet there’s a lot of other stuff on the list as well.”

That “other stuff” might be what makes or breaks commercial fusion power.

“Fusion needs to compete with other ways of making electricity and heat. If fusion power plants cost a lot more than other ways of making electricity, there’s not going to be many of them. There may be one that we take our kids to and show on a school field trip, and that’s it,” Conway said. “The economics of these things is going to really matter.”